Punctuation: it’s small, silent, and utterly powerful. These little marks guide our voices, shape our thoughts, and (let’s be honest) can make or break a sentence. But where did they come from? Who decided that a dot ends a sentence or a little curl means you’re asking a question?

Turns out, punctuation has a dramatic past—one that stretches from ancient scribes to modern texting. Let’s take a journey through time to explore how English punctuation came to be, and why it’s still evolving today.

No Punctuation, No Peace: The Chaos of Early Writing

In the earliest forms of writing—Sumerian cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and early Greek and Latin scripts—there were no punctuation marks at all. Not even spaces between words. Text was a relentless stream of letters with no breaks, pauses, or clues about where one sentence ended and another began.

This system, known as scriptio continua, made reading labor-intensive. Literacy was limited to elite scholars who could decipher entire pages without taking a breath.

Aristophanes of Byzantium: The First Dot-Dropper

Around 200 BCE, Aristophanes of Byzantium, a librarian in Alexandria, introduced a system of dots to help readers follow the rhythm of speech:

- A high dot for a long pause

- A middle dot for a moderate pause

- A low dot for a short pause

While this wasn’t punctuation as we know it, it laid the foundation for representing spoken intonation on the page. It was revolutionary—no longer did readers have to guess how a sentence was meant to sound.

Roman Interpuncts and the First Word Separation

The Romans took things a step further by introducing the interpunct (·)—a small centered dot used to separate words. While helpful, Roman grammar still leaned heavily on inflection and word order rather than on visual cues like punctuation.

Interestingly, Roman inscriptions often used these interpuncts in monumental texts carved in stone, suggesting that even public signage needed visual clarity. However, punctuation still hadn’t taken hold in manuscripts and everyday writing.

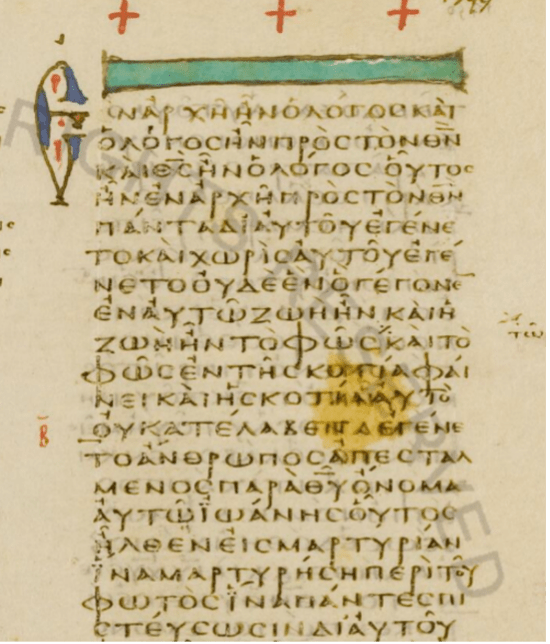

Medieval Monks and the Sacred Pause

In medieval Europe, Christian monks became the unlikely pioneers of more sophisticated punctuation. As they copied biblical texts by hand, they found it difficult to read and chant from dense, unbroken lines of Latin. So, they started marking texts with signs to guide oral reading—especially during religious services.

Some of the marks developed in this period include:

- Punctus versus (.) to indicate the end of a thought

- Punctus elevatus (⸒) for a rising intonation or continuation

- Punctus interrogativus (⸮) to signal a question

These early marks were more about rhetoric and cadence than grammar, but they made sacred texts far more accessible for reading aloud. Over time, the marks were adapted into more consistent systems of visual punctuation.

The Printing Press Changes Everything

The invention of the printing press in the 15th century demanded consistency. Without standardized punctuation, printers couldn’t reproduce books that made sense to readers across different regions.

This was when Aldus Manutius, a Venetian printer and publisher, made his mark—literally.

He:

- Popularized the comma

- Standardized the period

- Invented the semicolon

Manutius didn’t invent punctuation out of vanity—he did it to give writers more control over meaning. His semicolon offered a middle ground between a period and a comma, allowing for clarity and connection in complex ideas.

His innovations became widely accepted across Europe, setting the stage for modern punctuation’s role in structuring grammar rather than merely guiding voice.

The Rise of English Punctuation in the Renaissance

As English began to evolve into a standardized written language, punctuation took on a larger role in defining sentence structure. Prior to this, writers often punctuated based on personal style or local dialect.

The 16th and 17th centuries saw a proliferation of grammar manuals that sought to codify punctuation for the first time. Printers and scholars began to agree on what punctuation meant—not just how it sounded.

During this time:

- The colon was used to separate independent clauses or introduce lists.

- The comma became essential in setting off modifiers and phrases.

- The period came to indicate a complete sentence or finished thought.

Punctuation was no longer just for the reader—it was a tool for the writer to sculpt meaning.

The Exclamation Mark: From Latin Joy to Printed Drama

The exclamation mark traces its origins to the Latin word io—an expression of joy or triumph. Early scribes stacked the “I” over the “O,” which over time evolved into the vertical line and dot we use today.

Despite its ancient beginnings, the exclamation mark wasn’t commonly used until the 17th and 18th centuries. Even then, it was reserved for religious exclamations, poetic declarations, and dramatic speeches.

It wasn’t until modern printing—and eventually the internet—that it became the energetic punctuation we use (and overuse) in everyday writing.

The Question Mark: Quaestio Curled

Like the exclamation mark, the question mark has Latin roots—specifically the word quaestio (meaning “question”). Medieval scribes abbreviated it as “qo,” and gradually stylized it into the symbol we know today.

The mark began appearing in printed books during the late Middle Ages, but it wasn’t standardized until the printing press era. Once formalized, it became essential in distinguishing interrogative sentences from statements.

Its visual design—a curve with a dot beneath—has remained remarkably unchanged since the Renaissance.

The Hyphen: A Scribe’s Lifesaver

The hyphen began as a tool for scribes to indicate line breaks within a word—a necessity when writing on expensive parchment with limited space.

Over time, it took on new responsibilities:

- Linking compound words (e.g., well-known, mother-in-law)

- Separating prefixes from root words (e.g., re-enter)

- Avoiding ambiguity (e.g., “small-business owner” vs. “small business owner”)

Despite its utility, the hyphen has been slowly disappearing in modern English. Many compound words now drop it altogether (e.g., email, website), though it still plays a crucial role in clarity and tone.

The Em Dash: Long, Loud, and Literary

The em dash (—)—named for being the width of a capital “M” in typesetting—emerged in the 18th century as a way to create dramatic pauses, interruptions, or parenthetical thoughts.

It was especially beloved by authors like Emily Dickinson and Jane Austen, who used it liberally to shape the rhythm and tone of their prose.

Unlike the comma or semicolon, the em dash offers flexibility and flair. It’s less rigid than parentheses, more emphatic than commas, and perfect for blog posts, fiction, and creative nonfiction.

The Apostrophe: Possession and Contraction

First introduced into English in the 1500s, the apostrophe was originally used to show omitted letters in contractions or poetic abbreviations (e.g., o’er for over).

Soon, it also came to mark possessive nouns, a role it still holds today. The rules surrounding apostrophes in possessives (especially plural ones) have been debated ever since—just ask any grammar teacher.

Interestingly, the apostrophe is one of the most misused punctuation marks today—thanks in part to signs like “banana’s for sale” and “open Sunday’s.”

Quotation Marks: Marginal Beginnings

Quotation marks first appeared in 16th-century books as marks in the margins—used to indicate passages that were noteworthy or borrowed from other works.

Eventually, these marks migrated to the body of the text and became a standard way to denote direct speech. Over the centuries, the rules for their usage evolved and split regionally:

- In American English, double quotes (“ ”) are standard, with single quotes (‘ ’) used for quotes within quotes.

- In British English, the reverse is often preferred.

Today, quotation marks are also used for emphasis, sarcasm, and as typographic tools in titles and informal communication.

The Ellipsis: From Omission to Expression

The ellipsis (three dots …) was originally used in academic writing to signal omitted text in a quotation.

In literature, it evolved into a tool to show trailing thoughts, pauses, or silence. In modern writing—especially emails and texting—the ellipsis often conveys hesitation, awkwardness, or passive-aggression.

Like the em dash, the ellipsis is punctuation with personality. It doesn’t just clarify meaning—it suggests emotion.

Final Thoughts: Punctuation as Living Language

Punctuation isn’t a static set of rules—it’s an evolving, expressive system that mirrors how we speak, think, and feel. These marks are more than grammar—they’re rhythm, tone, clarity, and sometimes chaos.

From ancient scrolls to the printing press, from monks to memes, punctuation has helped humans share ideas clearly for centuries. And as language keeps changing—so will punctuation.

What’s Your Favorite Punctuation Mark?

Is there a mark you adore—the em dash, the semicolon, the always-controversial Oxford comma?

👇 Share your favorite punctuation symbol in the comments and tell us why it deserves the spotlight.

📣 Spread the punctuation love by sharing this post with your fellow word nerds!

📬 Subscribe for more writing deep-dives, grammar giggles, and language lore.

Let’s celebrate the little marks that do so much.

Leave a comment