Introduction

As a general rule warrior have always been popular in the imagination of man. Spartans, Gladiators, Assassins, Ninja and the modern Secret Operative; they all hold a place in both the annals of history and within the scope of myth and fantasy. Myth, legend and literature have followed their stories through oral telling’s to film and literature still popular today. Perhaps no group, however, has held quite a hold on the imagination quite like the Templar.

The very name congers up so many images, all differing based on who is hearing it. For some it is the name of the original Paladins, holy warriors bent on serving in blood and steal rather than with humble prayer. For others it brings up the image of conspiracies and control, of lost treasures and sacred relics. Still others have darker imaginings of satanic blood rituals and magic come to life.

The truth is of course far more mondain than the stories may have led us to believe but that does not make this order any less exciting to study or their lives any less fascinating. Separating the truth from the fiction can be a daunting task but it takes us on a journey well worth taking and in the end that is what true history is all about.

The Real Story

The Origins of the Templars

To have become so well-known, the origins of the Knights Templar are very humble. They began in 1119, 20 years after the capture of Jerusalem, with only 9 founding members. [1] The group was started by Hugh de Payne and Godfrey de Saint Omar and the idea was simple. A group of knights would live the austere life of monks with their only function being to serve God and protect the pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land to visit holy site This was a much necessary service. In the Easter of 1119 700 hundred pilgrims were attacked on their way to the river Jordan. Neary half of them did not survive.[2] This was a great worry to the leaders of the Crusades and the rulers of the Latin East.

That same year, two noblemen from France came to visit the court of Baldwin II. These men, mentioned above, Hugh de Payne and Godfrey de Saint Omar presented the idea of a monastic order whose chief purpose would be to protect pilgrims and those living in the Holy Lands. They would be warriors of the highest caliber, devoted not to the service of a crown but to the service of God.[3]

The idea was revolutionary because of it the contrasts in the ideals of monks and knights. Knights were warriors, killers. To kill was the greatest of sins and the very anthesis of what it was to be a monk! They tended to live of the riches of their plunder and were heavily lauded for their campaigns. Monks on the other hand, lived in austerity out of the limelight and in service to God. Had the idea been proposed before the Crusades, it is likely that Baldwin might have laughed them out of court or charged them with heresy; but the Crusades were in and of themselves and contrast of ideals and Baldwin knew it.

The Crusades, you see were something unique in the history of Europe, a Holy War. This Holy War was justified in the eyes of the Church through the writings of Saint Augustine of Hippo. He said that, “The real evils in war are love of violence, revengeful cruelty, fierce and implacable enmity, wild resistance, and the lust of power, and such like; and it is generally to punish these things, when force is required to inflict the punishment, that, in obedience to God or some lawful authority, good men undertake wars, when they find themselves in such a position as regards the conduct of human affairs, that right conduct requires them to act, or to make others act, in this way.”[4]

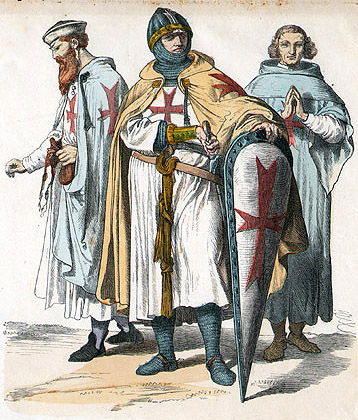

Like all Crusaders, the Templars were promised remission of sins for their deed because it was deemed that the acts of war the undertook were for the glory of God and that they were acting under his will.[5] Unlike most Crusaders, they quickly grew in prestige, however. Their group quickly swelled from 9 members to 300 by the time William of Tyre would write about them in his A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea in 1167.Though the knights had taken vows of poverty, and in the early years of their establishment were propagated as having to men per horse, an image which would become part of their seal as seen in the image above[6] , they would be well endowed by both the clergy and crown alike.

The white habit[7], for which they would become famous for wearing in later years, was first assigned to them 9 years after their founding by a council of clergy in France by the order of Pope Honorius.[8] Perhaps the most infamous symbol of the Templar that can be traced to reality is there home, The Temple of Solomon. The white habit[9], for which they would become famous for wearing in later years, was first assigned to them 9 years after their founding by a council of clergy in France by the order of Pope Honorius.[10] Perhaps the most infamous symbol of the Templar that can be traced to reality is there home, The Temple of Solomon. Upon taking the temple as their home, the Knights Templar henceforth became the Knighthood of the Temple of Solomon, having prior to that been called the Poor-Fellow Soldiers of Jesus Christ.[11]

Nobody knows for sure if the site truly was the ruins of the Temple of Solomon. Prior to the retaking of Jerusalem, the existing temple has been home to the Al-Aqsa mosque. Built in the seventh century, it was considered to be quite holy for the Muslims living in Jerusalem.[12] If it truly was the Temple of Solomon, it would have once been home to great treasures. rumors of excavations under the temple still persist today but rather or not they found a great or holy treasure is up for great debate.

One of the biggest supporters of the order was Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, one of the most notable churchmen of his day. He admired their devotion to God above worldly pleasures. Bernard was a known critic of contemporary knights, questioning their manhood do their dawning of silk and bejeweled cloths and long, curly locks.[13] Barnard himself chose to live a life of austerity and poverty much in contrast the average European priest or monk, one dedicated to hard labor and study rather than art and finery.[14]

This was a man known for his piety and his fiery temper. He even was known to lecture the pope! There could be no better ally for the Templars. Bernard was long disgusted by the blazon amorality of the contemporary knights and saw the Templars as a new knighthood, something like his own monastic order, created to serve God and not vice.

Not only was he their biggest supporter but it would be Bernard who would create the “Templar Rule”, a document dictating the rules and ways of life for the order. He presented this rule at the 1129 council of Troy where the Templars were officially accepted by the Church. This rule would dictate every aspect of life for the Templars, a way of life that was as vastly different from the contemporary knighthood as Bernard’s order was from the contemporary abbey; a way of life that would set the Templars apart from all others[15]

Life, Laws and Governances

The Templars have long been idolized as treasure hunters, mysterious men with an even more mysterious agenda but as seen by their early history; the reality is however is that the Templars were not in fact great treasure hunters. They held great wealth and had many land holdings, more on that later, but their lives were quite austere. Most of their time was spent in prayer, battle or training for battle. They had but one job, defend the poor, widows, orphans, and churches. They took meals in silence, except for the reading of scripture. This was the life Bernard had imagined for them and had set them up for with his 1129 rule.[16]

There were over 680 rules dictating everything from daily life, order hierarchy, battle protocol and prayers. The rules were divided into seven sections but only three can found in the 1886 edition compiled by Henri de Curzon, the most complete edition still available. The original was lost to time after the Templar Trials, so many of these rules are currently unknown.[17] Not all of these rules were created in 1129, but rather were added over the 150 years from the creation of the rule to the fall of the order.[18]

The seven sections of the rule were: The Primitive Rule, the Hierarchical Statutes, Penances, Conventual Life, the Holding of Ordinary Chapters, Further Details on Penances and, finally, Reception into the Order.[19] A few of those will be reviewed here.

The Primitive Rule

The Primitive Rule was originally composed in Latin at the council of Troy and was based on modified versions of existing practices of the Templars.[20] The first 10 sections or so of the Primitive Rule focuses on the founding of the order and the happenings of the council itself while later rules in the section focused on who and how one could become a member, how life was to be lived and even on bedlinen. [21]

According to the Primitive Rule any man or knight could be brought into the order so long as they took the vows and were willing to live a life of simplicity and devotion. The rule however expressed that children should not be allowed to join but rather “he who wishes to give his child eternally to the order of knighthood should bring him up until such time as he is able to bear arms with vigor and rid the land of the enemies of Jesus Christ”[22] Women were expressly forbidden from entering the order and the Temple itself. In fact, it was forbidden to embrace or kiss any woman, even one’s own mother, for fear that the Templar should be led astray by her.[23]

Hierarchical Statutes and The Order Structure

This section covered the status quo of the Templar House. That is to say the rules of each individual, what was granted of them and what was expected of them in return. For instance, a knight in the presence of the Master was not able to do anything such as bathe, joust or even stand if in penance before the Master unless he so gave permission.[24]

The Master was the head of the order and was, until its fall, based in the Latin East. He was elected for life at an assembly made up of all of the brothers headquartered in the Latin East. This would have been in Acre from 1191-1291, Jerusalem prior and Cyprus from 1291 on. [25] He was the one who would lead the brothers of the order into battle, conduct their secular affairs and was their spiritual leader and guide, much the same way as the Pope was the spiritual representation for God within the Church. [26]

The Master had duties as well. The Rule calls for him to wash the feet of paupers and give them bread, clothing and shoes wherever he be on Maundy Thursday. Likewise, if he was in the temple five paupers would be allowed to eat therein. He could not sell land or castles without the Templar chapter’s permission.[27]

Below the Master was the Seneschal. He was the Master’s “right hand man”. He carried the Templar flag or standard into battle when not done by the Marshall. In later times he would be known as the Grand Commander.[28] When the Master could not be somewhere, the Seneschal would go in his stead.[29] Many Seneschal’s became Masters themselves.[30]

Bellow the Seneschal was the Marshal. He could not hold chapter meetings without the Master, but it was the Marshall who made the call to arms in battle.[31]

These are but some of the roles discussed in the Hierarchical Statutes. The Hierarchical Statutes also commanded how Templars should march, make camp and care for their sick. For instance, there was a special table for the sick who could not, for their health, eat the food of the brothers, though those who were ill but well enough to, were ordered to eat in the convent. There were rules about what foods the ill could be given too. For instance, no sick brother could be given cheese![32]

Penances

The section entitled Penances, gives great detail on what could get a brother expelled from the Templars. The crimes range from killing a Christian to heresy to having contact with a woman or refusing to do battle.[33] These are only a handful of “sins” that could make someone lose their place in the order.

The section also details what can be done in penance for misdeeds. He must first renounce the world and commit to obedience to God and the order.

He must then say that he is ““…willing and I promise to serve the Rule of the Knights of Christ and of His knighthood with the help of God for the reward of eternal life, so that from this day I shall not be allowed to shake my neck free of the yoke of the Rule; and so that this petition of my profession may be firmly kept, I hand over this written document in the presence of the brothers forever, and with my hand I place it at the foot of the altar which is consecrated in honor of almighty God and of the blessed Mary and all the saints. And henceforth I promise obedience to God and this house, and to live without property, and to maintain chastity according to the precept of the lord pope, and firmly to keep the way of life of the brothers of the house of the Knights of Christ.”[34] He would then lay down on the alter and pray to God for life and forgiveness.

Reception into the Order or Becoming a Templar.

As stated earlier, not just anyone could become a Templar. Children would not be accepted into the order until they were trained and grown.

Members of the order were to avoid the company of women at all costs so unlike other military orders and religious organizations, women were “forbidden” from joining the ranks of the Templars. Though it should be noted that before 1129, this was not the case and there were even some noted “sisters” of the order. However, as a general rule females were not permitted to be a part of said the Temple. The notable exceptions usually joined with their husbands such as the case of Aiglina of Sales and Borella Bernard.[35]

The rule against women may very well have been linked to its connection to Bernard of Clairvaux and the Cistercian Order.[36] There does seem to be some exceptions to this rule however as there was even once a female commander of the Templars, Ermengarde of Oluja who joined the order in 1196 with her husband Gombau.[37]

Those who could be received into the order must first have the rules of the orders read to them and promise to devote their lives to God and to the order. If they could not, then they were turned away. If they did make these vows than he could join.[38] A man could join for life or for a temporary a “fixed term”. It did not matter if the latter had any formal combat or religious training. [39]

An excommunicated knight could join the order under certain circumstances. He had to go before the bishop and confess his sins and desire to join the order. He must renounce the world and give himself wholly to God. If the bishop absolved him of the sin, he could join the order. Otherwise, he could not.[40]

Life in the Order

Life in the order was harsh and simple. As Bernard of Clairvaux pointed out, these were not secular men but holy warriors of God, held to a much higher moral standard. Knights in the order had no choice but to “observe unfailing obedience to the master … as soon as an order has been given by the master or his appointed representative, brothers should put it into action without delay as if it were God’s command … no brother [should] fight nor rest according to his own volition but must put all his effort into obeying the master so that he be able to imitate the word of the Lord: ‘I did not come to fulfill my own will but that of him who sent me’.”[41]

They owned nothing of their own and carried only the money needed for travel or business. They wore only what they were told to wore and only true knights of the order were allowed to take up the white habit.[42] By the time the order began to gain wealth and prestige each knight was given 3 horses and their own equipment which they must care for daily.[43]

They were forbidden from ornate bridles and clothing and must never bedeck themselves with jewel or stylish locks.[44] They repaired their own clothing and set out to do whatever task was needed for the common good of the order when time was free.[45]

The day for a brother of the Templar ordered varied depending if it was war or peace time. They attended 7 services and prayer meetings throughout the day.[46] Typically during peace time their days began at 4 a.m.[47] and ended after 8 PM. They would sleep until midnight when they would rise for Martins and then return back to bed until the next day at 4 AM.[48]

Meals were given twice a day, at noon and dusk. They ate meat on all days but Friday, eating their meals in silence save for the reading of scripture.[49] They always ate in pairs, on and off of the battlefield. It might have indeed been a lonely life, even by monastic standards but the Templar was to crave only the company of his brothers and Christ. He was to have no need of wife, children or family.[50]

Banking and Wealth

The Templar knights were as individuals quite poor but as an organization, they were splendidly wealthy. If Forbes had a list of the most power and wealthy organizations in all the world, they would have been second only to the Church itself![51] Master Templar Geoffrey Fitz Stephen would compile a list of their holdings.

Among them were manor houses and homesteads, sheep farms and water mills, churches, markets, forests, fairs, estates and even isolated villages with serfs who lived and worked their part of the year. [52] These holdings could be found all of Europe, even after the fall of the Latin East and only grew larger with time.[53]

The Templars did not have to pay taxes and would enjoy many other luxuries such as exclusive and sometimes toll-free use of harbors for trade, such as the one in Marseille. These harbors were used to send goods back to the order in the East as well as bringing pilgrims and merchants to sell their wares and pray.

They had powerful friends and enjoyed, at the time, good connections with leading secular rulers, especially in France in England. In 1202 a Templar was even made treasurer for the French crown.[54]

Among common folk and nobility alike they served as trusted advisors and financers. They did everything from legitimizing holy relics[55] and drawing up charters and documents to providing loans[56] and of course international banking, which they invented.

A pilgrim could take their gold to one Templar holding, get a note and take it to another Templar holding to receive their gold. It was the first form of ATM banking and the first check.[57] This, along with their other holdings above made the Templars not only fabulously wealthy but powerful as well. Unfortunately, with that power, comes lust and envy. Powerful enemies were soon to come for the Templars and it in their wake, the order would be destroyed, living only in the shadow of memory and myth.

The Fall of the Templars

Friday the 13th is a day of superstition. Many believe that it is the unluckiest of all days and that bad luck has its roots in the history of the Templars themselves for it was the day that doomed the order forever, the day the Templars faced their own Order 66 and their story fell into myth and legend!

Friday the 13th

It was Friday the 13th of October 1307. Many of the Templars, along with their grand master Jacques de Molay were called to Paris, France and arrested by Phillip on charges of heresy. Heresy was the worst crime imaginable in the medieval world, worse yet than treason against the king for heresy was treason against the highest rulers of all. It was treason of the Church and worst of all, against God. The charges said that they refused the sacraments, denied Christ as the son of God and spat on the Cross.[58]

They were accused of worshiping an idol, of satanic rituals in their induction ceremonies. It was said that they committed acts of sodomy, kissing new members of the order on the mouth, butt and spine.[59]

These kind of accusations had been used to denounce pope’s kings and prophets for centuries and were certainly nothing new. It was very easy for Phillip IV and others like him to question the Templar’s motives and background. It would not have been too far-fetched for anyone to make the claim from there that the power the Templar’s had gained was not from God as they claimed but came from Satan whom they were said to worship. In the medieval world, such an accusation carried a heavy weight with it.

So it was with these charges in hand that the arrest warrant came for the Templars on that faithful October day. It is said that the confessions the Templars made to these crimes were tortured out of them. Considering that in countries such as England, where torture was illegal, the rate of confessions was much lower than in France and other countries like it, help support this assumption.[60]

At any rate, the damage was done. Molay and other Templar leaders had confessed to the crimes, only retracting these statements when standing before a papal committee. They did indeed say they had been tortured and Pope Clement, outraged, suspended the legal proceedings.[61]

Unfortunately, Pope Clement was basically under house arrest at the time so this suspension of proceedings did not last long and in May of 1310, Phillip had 108 Templars burned at the stake. Jacques de Molay would follow them to the fire in March of 1314.

With these men, the Templar order, as it had once existed with no more. As he burned Molay warned that within one year’s time, Philip and Clement would meet him again and face judgment before God. Hauntingly, this would come to pass, the last victory perhaps, of the Holy Order.[62]

The Myths and Legends

Numerous myths and legends have risen up about the Templars, perhaps even more so because of the gruesome way their order came to an end. There exists in the Reddit boards and books posted by conspiracy theorists, in the myths and legends surrounding holy relics like the Holy Grail. They are likely the inspiration behind the Dungeons and Dragons archetype of the Paladin. Before we take a glance at the history of the Templar, let’s take a look at the popular view of this order and just how far it falls of the path of truth, or perhaps how close!

Holy Relics

One of the most prevailing myths about the Templars is that beyond all of their other treasures, they held some of the most valuable items on Earth, Holy Relics of Christ like the Holy Grail The very thought of these relics has captured the imagination for centuries and the myth still looms today.

The Holy Grail is sometimes depicted as a cup and sometimes as a chalice. Sometimes it is depicted as the cup or bowl Jesus drank or ate from in the last supper. At other times it is thought to be something used by Joseph of Arimathea to collect his blood at the Crucifixion.

In other works, such as Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival it is depicted as a stone.[63] It is often paired with the story of King Arthur and his knights. The connection with the Templars did not come about until the 13th century but it is a connection that has long prevailed. If the Templars did indeed have the grail and it held the power that mystics and mythology report, then they would have had the holiest and most powerful of relics on their hands.

It was said to have healing powers, saving the pure of heart from any illness or injury. It could broaden the human mind, provide endless food or drink and its connection to Christ would alone would have made it priceless.[64]

Although the Templars do not appear connected by name to the Grail in earlier works it is believed that they are referenced all the same. Even before the crushing of the order that faithful Friday the 13th, 1307, they were becoming the stuff of legend.

The character of Galaad, Arthur’s purist and most noble knight, is thought to be symbol for the Templars. He carries the banner of a red cross on a white standard and is followed by 33 holy men wearing habits eerily similar to those worn by the brothers of the Templar order.[65] Some people believe that before their fall, the Templars hid the grail from Phillip () and the search for this artifact continues from enthusiasts today.

Conspiracies and Coverups

There are those who believe that the Friday the 13th disaster had less to do with heresy and farm more to do with a cover up by the Church and the crown. Conspiracy theories have abounded about the Templers. Some involve the holy grail, others something else. If you’ve read Dan Brown’s DaVinci Code, then you are probably aware of this particular theory. It has taken hold in many books and films over the years, with Brown’s probably being among the most famous.

The theory postulates that the Templars were not in fact created to protect the pilgrims in the East but rather to protect the bloodline of Christ. It states that Christ was married and had a child with Mary Magdalene and that was the treasure they were to protect. The church did not want this secret getting out so they had the Templars framed and murdered.[66]

Other theories state that the Templars hid a vast treasure, unearthed from the Temple of Solomon, just waiting to be found. Theories like this one have also long been popular in films such as National Treasure and Indiana Jones. Indeed, even on the History Channel, treasure hunters have gone looking to see if they could find the lost treasure of the Templars.

Closing Thoughts

The rumors about the Templars are larger than life and they have lived long after the order has fallen. Some say the Templars live in completely in the guise of new secret societies like The Free Masons. Others say many Templars themselves escaped execution and dissolved into the shadows, waiting for their time to ride again.

Believe the conspiracies and myths or not, The Templars were a force to be reckoned with. There were amazing battles and victories and terrifying losses. Secret rituals and holdings we know nothing about still wait to be discovered. Their banking methods revolutionized the way business is done even today! Their own history is fascinating and too grand to even begin to truly elaborate on in such a short time. My only hope is that this brief glimpse into the Templars raises the interest of you dear reader as much as it has fascinated me.

[1] Riley-Smith Jonathan Riley-Smith, The Crusades: A History (Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), http://www.vlebooks.com/vleweb/product/openreader?id=none&isbn=9781472508799&uid=none.

[2] Sean Martin, The Knights Templar, 1st Thunde (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2004).

[3] Martin.

[4] S.J. Allen and Emilie Amt, The Crusades: A Reader, The Crusades: A Reader, 2nd ed. (Ontario, 2014).

[5] William of Tyre, Emily Atwater Babcock and August C. Krey, A History of Deeds done Beyond the Sea (New York: Columbia University Press, 1943)525.

[6] Thomas Andrew Archer and Charles Lethbridge Kingsford, The Crusades, the Story of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, vol. fiches 2,2 (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1894), http://catalog.crl.edu/record=b1501295.

[7] Diario Gráfico, “Bernard’s Chosen: The Knights Templar,” Medieval Warfare 6, no. 5 (2016): 38–39, https://www.jstor.org/stable/48578611.

[8] William of Tyre, Emily Atwater Babcock, and August C Krey, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea (New York: Columbia University Press, 1943).

[9] Gráfico, “Bernard’s Chosen: The Knights Templar.”

[10] of Tyre, Babcock, and Krey, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea.525

[11] Charles G Addison, The History of the Knights Templars (New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing, 2012).

[12] Peter Konieczny, “Who Were the Templars,” Medieval Warfare 6, no. 5 (2016): 6–9.

[13] Andrew Holt, “Bernard of Clairvaux and the Templars: The New Knighthood,” Medieval Warfare 6, no. 5 (2016): 13–17, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/48578606.

[14] Dan Jones, The Templars (New York, New York: Viking, 2017).36

[15] Holt, “Bernard of Clairvaux and the Templars: The New Knighthood.”

[16] Holt.

[17] J.M. Upton-Ward, The Rule of the Templars, Repr. in p, vol. 4 (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1999).

[18] Upton-Ward.

[19] Upton-Ward.

[20] Upton-Ward.

[21] Upton-Ward.

[22] Upton-Ward.

[23] Upton Ward.

[24] Upton-Ward, The Rule of the Templars.

[25] Helen Nicholson, The Knights Templar: A Brief History of the Warrior Order, 2nd ed. (London: Constable and Robinson, 2010).

[27] Upton-Ward, The Rule of the Templars.

[28] Karen Ralls, Knights Templar Encylopedia: The Essential Guide to the People, Places, Events and Symbols of the Order of the Temple., ed. Gina Talucci (Pompton Plains: Career Press, 2007).

[29] Upton-Ward, The Rule of the Templars.

[30] Martin, The Knights Templar.

[31] Upton-Ward, The Rule of the Templars.

[32] Upton-Ward.

[33] Upton-Ward.

[34]Upton-Ward.

[35] Myra Miranda Bom, Women in the Military Orders of the Crusades (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

[36] Bom.

[37] Bom.

[38] Upton-Ward, The Rule of the Templars.

[39] Jones, The Templars.

[40] Upton-Ward, The Rule of the Templars.

[41] John Howe, “Military Secretsof the Knights Templar: The Rule,” Medieval Warfare 6, no. 5 (2016): 20–25.

[42] Sharan Newman, The Real History Behind the Templars (London, 2007).

[43] Newman.

[44] Upton-Ward, The Rule of the Templars.

[45] Bernard of Clairvoaux, “In Praise of the New Knighthood,” in The Crusades: A Reader, ed. Amt. Emilie Allen, S.J. (Ontario: University of Toronto Press, 2014), 128–31.

[46] Evelyn Lord, The Templar’s Curse (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2008).

[47] Upton-Ward, The Rule of the Templars.

[48] Lord, The Templar’s Curse.

[49] Martin, The Knights Templar.

[50] Howe, “Military Secretsof the Knights Templar: The Rule.”

[51] Tracy Bacal, “Buried:Knights Templar and the Holy Grail: Holy Grail Unearthed,” 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMJY4kmVKgY.

[53] Jones.

[54] Jones.

[55] Bacal.

[56] Jones.

[57] Bacal.

[58] Clement (V), “Papal Bull Supressing the Templars,” in The Crusades: A Reader, ed. Emilie Amt and S.J. Allen (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014), 357–63.

[59] Malcom Barber, Trial of the Templars, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge Univiersity Press, 2006).

[60] Martin, The Knights Templar.

[61] Martin.

[62] Martin.

[63] MINA SEHDEV, “TEMPLARS AND THE HOLY GRAIL. A CROSS-REFERENCE RELATIONSHIP IN AN ONTOPOIETIC PERSPECTIVE,” Agathos : An International Review of the Humanities and Social Sciences V, no. 1 (May 2014): 103–13, https://doaj.org/article/8e9e3cea5c8c4927aca7763984d70afa.

[64] SEHDEV.

[65] Helen Nicholson, Love, War and the Grail (Boston: Brill, 2001).

[66] Jones, The Templars.

Works Cited

Addison, Charles G. The History of the Knights Templars. New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing, 2012.

Allen, S.J., and Emilie Amt. The Crusades: A Reader. The Crusades: A Reader. 2nd ed. Ontario, 2014.

Archer, Thomas Andrew, and Charles Lethbridge Kingsford. The Crusades, the Story of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Vol. fiches 2,2. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1894.

Bacal, Tracy. “Buried:Knights Templar and the Holy Grail: Holy Grail Unearthed,” 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMJY4kmVKgY.

Barber, Malcom. Trial of the Templars. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge Univiersity Press, 2006.

Bom, Myra Miranda. Women in the Military Orders of the Crusades. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Clairvoaux, Bernard of. “In Praise of the New Knighthood.” In The Crusades: A Reader, edited by Amt. Emilie Allen, S.J., 128–31. Ontario: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Gilliman, Terry, and Terry Jones. Monty Python and the Holy Grail. United Kingdom: EMI Films, 1975.

Gráfico, Diario. “Bernard’s Chosen: The Knights Templar.” Medieval Warfare 6, no. 5 (2016): 38–39. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48578611.

Holt, Andrew. “Bernard of Clairvaux and the Templars: The New Knighthood.” Medieval Warfare 6, no. 5 (2016): 13–17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/48578606.

Howe, John. “Military Secretsof the Knights Templar: The Rule.” Medieval Warfare 6, no. 5 (2016): 20–25.

Jones, Dan. The Templars. New York, New York: Viking, 2017.

Konieczny, Peter. “Who Were the Templars.” Medieval Warfare 6, no. 5 (2016): 6–9.

Lord, Evelyn. The Templar’s Curse. New York: Taylor and Francis, 2008.

Martin, Sean. The Knights Templar. 1st Thunde. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2004.

Newman, Sharan. The Real History Behind the Templars. London, 2007.

Nicholson, Helen. Love, War and the Grail. Boston: Brill, 2001.

———. The Knights Templar: A Brief History of the Warrior Order. 2nd ed. London: Constable and Robinson, 2010.

of Tyre, William, Emily Atwater Babcock, and August C Krey. A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea. New York: Columbia University Press, 1943.

Ralls, Karen. Knights Templar Encylopedia: The Essential Guide to the People, Places, Events and Symbols of the Order of the Temple. Edited by Gina Talucci. Pompton Plains: Career Press, 2007.

Riley-Smith, Riley-Smith Jonathan. The Crusades: A History. Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. http://www.vlebooks.com/vleweb/product/openreader?id=none&isbn=9781472508799&uid=none.

SEHDEV, MINA. “TEMPLARS AND THE HOLY GRAIL. A CROSS-REFERENCE RELATIONSHIP IN AN ONTOPOIETIC PERSPECTIVE.” Agathos : An International Review of the Humanities and Social Sciences V, no. 1 (May 2014): 103–13. https://doaj.org/article/8e9e3cea5c8c4927aca7763984d70afa.

Upton-Ward, J.M. The Rule of the Templars. Repr. in p. Vol. 4. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1999.

(V), Clement. “Papal Bull Supressing the Templars.” In The Crusades: A Reader, edited by Emilie Amt and S.J. Allen, 357–63. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014.